As anxious as it makes me to think about The Future and What Happens After College, I’m going to be a senior this year and suppose I can’t avoid it forever. Also, Phil and Molly are making me think about it, as we have to give them a description of our dream jobs this week. It’s just an assignment, but it’s led me into a minor existential crisis the past couple days.

I’ve always been an indecisive person. While most people switch their major maybe a few times in college, I’ve changed mine no less than eight times before finally settling on my current degree, Cultural Anthropology.

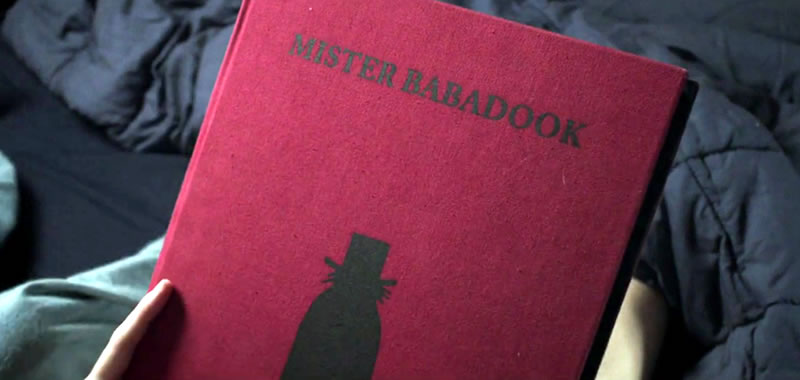

Growing up, I loved to read and write. I always had some novel or short story I was working on. So naturally, I started college as a Creative Writing major with the dream of becoming a writer. The thing is, it turns out I really hate English classes. I just felt like I was going nowhere. How was I going to actually make any meaningful change in the world by taking apart the rhetoric in Gilgamesh? (Not to say anything bad about English Lit folks—it’s just not my thing). That question took me on a prolonged detour with Public Health with plans of doing the Peace Corps and working in women’s health before finally settling on my current degree. Anthropology does, in an unexpected way, combine a lot of the aspects of the two fields I’d previously been torn between.

So fast forward back to week two of MISC, where I’m still trying to figure out exactly how I want to shape these new realizations into a career path for myself. And that, finally, brings us to the world of audio.

Hearing our mentors talk about radio and working on my own audio documentary project this week has made me think a lot more about pursuing it as a career. I think it’s both totally unexpected and totally natural that audio has made such a significant comeback in the 21st century. While it’s an old medium, not as flashy or immersive as film maybe, what it does is cater to is the go-go-go mentality we currently have as a society. It’s a rare form that you can consume while multitasking.

As a full-time student with two jobs, I don’t have a lot of free time to watch TV or read anything not related to school. But I do have time for podcasts. It’s the only kind of media I can consume consistently everyday, on my morning commute, as I deliver mail at work, as I make dinner, as I do dishes, as I fall asleep.

With NPR programs like Radiolab and This American Life leading the way, podcasts are increasingly becoming a source of entertainment and news for Americans. While the audience of podcasts still remains behind that of other media forms, it is steadily growing. As all of our radio mentors have talked about, the great thing about audio is that it’s much cheaper and more accessible to create as a solo freelancer. Audio lets you include more emotion than print without all of the people and equipment necessary for a professional-quality film. Audio requires only a journalist, a professional recorder, and editing software.

One of the main benefits of audio I’ve noticed during my own project is how you’re able to capture people’s emotion and personality more than you would be with print, while still being much less invasive film. The organization I’m working with serves weekly meals to women who have been affected by homelessness, poverty, the sex industry, and domestic violence. Not everyone wants their entire identity to be associated with a period of hardship they are going through.

Many of these women I interviewed are in very vulnerable positions and having their face on film could put them at risk. I feel I was able to have real conversations with all of the women I’ve spoken with, and I’m not confident I would have been as welcomed or given that same authenticity if I had a video camera in their face. It’s easier to forget about a recorder, which allowed us to have better conversations and also gave me a way of providing some of the women the anonymity they needed for their own safety. But I was still able to capture their voices and the overall feeling of the space in a more vivid way. It’s one thing to describe a scene, but it’s another to be able to actually hear the specific sounds in the room that made it feel so warm and welcoming- the dishes clinking, the doors opening, the conversations happening between old friends.

I’m much too indecisive to settle on any one medium just yet, but audio has definitely stepped up as my number one this past week. It’s an exciting and accessible medium that gives me a way to tell stories that matter in a creative and impactful way. Is it what I’m committing to for my whole life? I don’t know. But for this next week at least, that would be my answer.

–Kienna Kulzer