I have to tell you that I am deeply, fundamentally not at all a horror movie person. My horror meter peaks out at Stranger Things and that’s really pushing it. But somehow, after much poking and prodding from Atlas and Lucy (our cohort’s horror connoisseurs), this week we all sat together and watched The Babadook (2014).

The next morning, squished up next to one another in the living room before a seminar, Molly (MISC’s coordinator) teased and asked, “What can the Babadook teach us about social justice?” Now, we’re less than a week into the program, with 500 things flying through the air at any given time, but I can’t seem to escape one facetious comment. In this brief time I’ve found myself thinking deeply about a whole lot of things: well-told stories, systems of injustice, mobilizing meaningful change through media, and—bafflingly, of all things—The Babadook.

If this is sounding a little wacky, let me backtrack for a moment. On Tuesday, Outside podcast’s Peter Frick-Wright led us through a storytelling and audio production session. “At its most basic,” he began, “a story is a conflict and a resolution.” During the break, Isa prompted my favorite conversation during our time at camp with one probing question: how do you resolve a conflict about an ongoing, entrenched social issue?

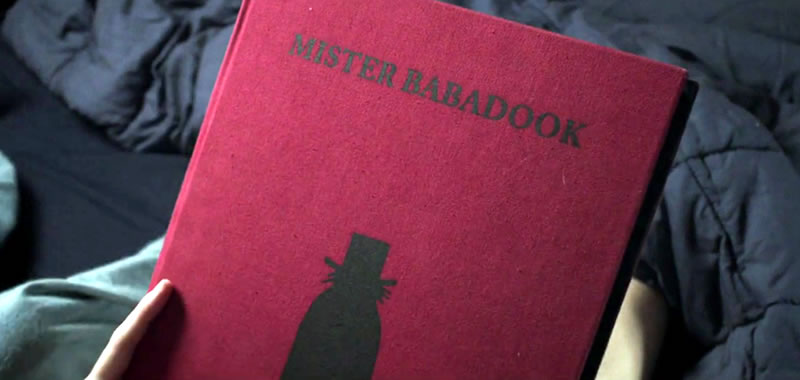

This warrants a quick summary (spoiler alert, sorry). Essentially, The Babadook follows a mother and son and their midnight hauntings by a shadowy, scythe-fingered creature called the Babadook. While the boy acknowledges the monster’s presence and prepares himself to fight back, the mother—who, after seven years, is still mourning the death of her husband and struggling to support her oddball, outcast son—dismisses his fears as childish ravings even in the midst of accelerating signs and bumps in the night.

“The more you deny me, the stronger I get,” the Babadook tells her via the world's creepiest, most disturbing children’s book. Denial leads to full-on Babadook possession and soon she’s chasing her son around the house with a massive kitchen knife. The climax takes us to the basement where the boy’s booby traps force his possessed mother to confront the monster head-on. “You have to let it go!” he yells. She vomits up a stream of black sludge. “I think this is a metaphor for grief!!” a member of our group shouts mid-scene during our viewing. Evidently. The Babadook closes out with mother and son gardening in the sun-saturated backyard. After gathering a bowl full of worms, the mother makes her way down the basement stairs and sets the bowl down on the concrete floor. Something shifts in the shadows and the bowl slides from the sunny patch of floor to the shaded corner, pulled by phantom limbs. She hasn’t defeated the Babadook, we’re meant to understand, but she has carved out a space for it. She is healing her grief by accommodating it.

This is a long-winded, but I think useful way to get at the intrinsic challenges of fusing media storytelling with social justice. Isa’s question—“how do you resolve a conflict that has no obvious ending?”—points to a fundamental question that I hope to wrestle with for the rest of the summer: do the formulaic demands of storytelling ontologically diverge from the messy, entrenched realities of injustice and oppression? “Your story can’t solve poverty in America, so how do you resolve a story about poverty?” Peter’s answer went something like this: to find resolution in an ongoing conflict, pivot. “Find a seam or an avenue in the story that will get you to the landing your audience needs.” Essentially, look harder—things aren’t always what they appear and resolutions will rarely look the way you’d expect them to.

What can the Babadook teach us about social justice? Sometimes you have to pivot in unexpected directions for your story to find its natural resolution. Sometimes instead of killing the monster, you let it shack up in your basement.

–Emily Curtis